Indigenous Foodways: What if Food Could be Medicine and Restore Cultural Lifeways?

By Kaylah Kilby

What if food could do more than nourish our bodies - what if it could restore culture, heal communities, and reclaim food sovereignty? For the Wabanaki Tribes of Maine, returning to ancestral foodways offersexactlythat. After centuries of colonial disruption, loss of land, and forced dietary changes,reviving traditional foodways isemergingas a path toward health and cultural survival.

Figure 1. Mural of Wabanki people on display at an exhibit at the Abbe Museum in Bar

Harbor. 2

Figure 1. Mural of Wabanki people on display at an exhibit at the Abbe Museum in Bar

Harbor. 2

Pre-Colonization

Wabanaki food systems were rooted in balance with the seasons, land, and community.1 These diets supported not only physical health, but spiritual, emotional, and relational well-being.2 Colonization severed these lifeways,–replacing nutrient-rich, land-based foods with processed commodity rations and disconnection from ancestral knowledge.3 Today, revitalizing traditional foodways offers a holistic path forward.

Health Disparities

In Maine, Indigenous peoples have a life expectancy 10-14 years shorter than the general population.4 They face higher rates of chronic illness like diabetes and its related comorbidities, addictions (tobacco, alcohol, and other substances), and obesity.4 Nearly 30% live in poverty, and over 23% lack health insurance.5 Geographic location, limited access to healthy food, and systemic underinvestment in healthcare contribute to these outcomes. These are not just social statistics, they highlight the challenges of historical and ongoing disconnection from land, culture, and traditional foodways.

The Role of Traditional Foodways in Health

Wabanaki communities once followed the natural rhythms of the seasons: planting corn on the riverbanks in spring, harvesting coastal fish and gathering berries in summer, hunting wild game in winter.6,7 These weren’t just foods; they were part of a larger system of knowledge sharing, identity, and spiritual reciprocity.8 Reconnecting with these practices strengthens connections, supports holistic well-being, and promotes sustainable land stewardship. Building on these ancestral foodways, the Indigenous Nourishment Model offers a modern framework that honors this holistic approach to health and well-being.

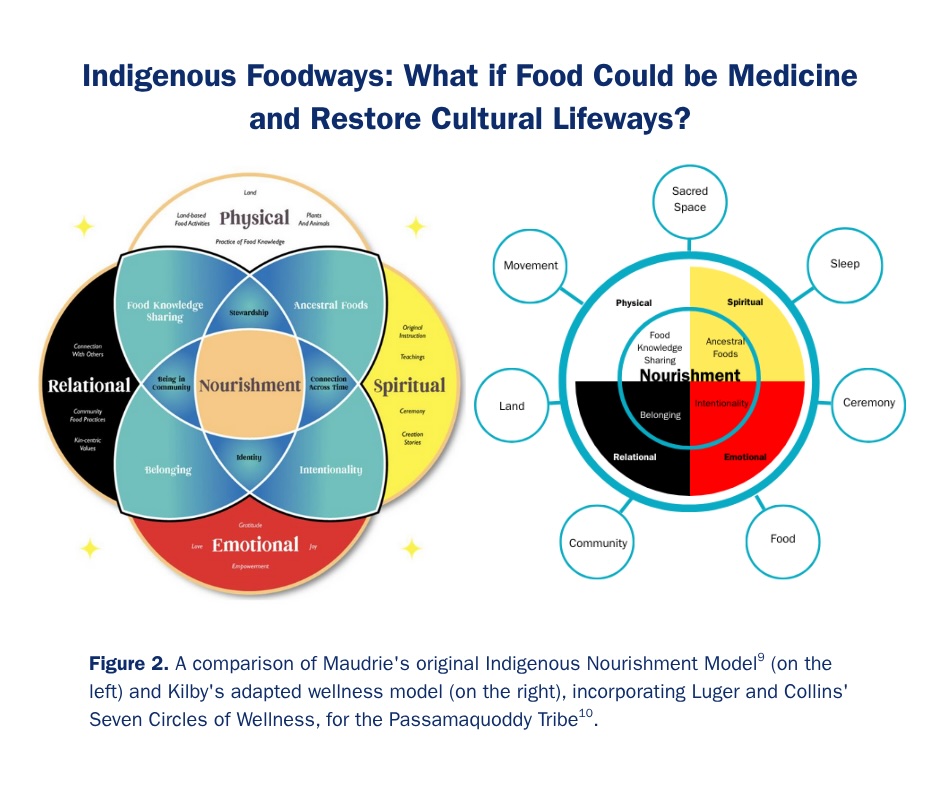

Introducing the Indigenous Nourishment Model (INM)

The Indigenous Nourishment Model (INM) is a framework that emphasizes the holistic nature of nourishment and the importance of considering multiple dimensions of wellbeing in nutrition and practice.9 Developed with American Indian and Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander people urban residents in Baltimore and Minneapolis, it includes four interconnected domains of nourishment: physical, spiritual, emotional, and relational.9 It emphasizes that nourishment is not just the physical food that feeds the body, rather the IMN recognizes the interconnectedness of heart, body, spirit, and relationships in Indigenous communities.9 The model was adapted to include the Seven Circles of Wellness introduced by Luger and Collins.10 This author culturally grounded the adapted model on the right to serve local communities like the Passamaquoddy Tribe of Maine, helping professionals to shift to a broader vision of nutrition and wellness.

Conclusion & Call to Action

Ultimately, revitalizing Indigenous foodways is more than restoring diets–it’s an act of healing, cultural affirmation, and reconciliation. It’s a step toward improving health outcomes while honoring cultural identity and traditions.

As nutrition professionals, we must advocate for integrating Indigenous foodways into modern nutrition practice. Because food is more than just sustenance; it is a way of life.

Share this story to spread awareness on how we can better support Indigenous communities in their wellness and food sovereignty.

References:

- A new beginning for Wabanaki land relationships. My Maine Stories. https://www.mainememory.net/sitebuilder/site/3089/page/4890/display#:~:text=The%20tribes%20lived%20in%20harmony,integral%20part%20of%20daily%20living

- About the Wabanaki Nations — Abbe Museum. Abbe Museum. https://www.abbemuseum.org/about-the-wabanaki-nations

- Indigenous foods. NICOA - National Indian Council on Aging.https://www.nicoa.org/elder-resources/indigenous-foods/#:~:text=The%20federal%20government%20discouraged%20American,spam

- Health Status and Needs Assessment of Native Americans in Maine: Final Report. (2000). https://www1.maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/files/nar/nar.htm

- Jernigan V J, Huyser K R, Valdes J, Simonds V W. Tribal Food Security Resources: A Guide for Tribal Leaders During the COVID-19 Pandemic & Recovery Period.; 2017. https://www.anawestern.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Tribal-Food-Security-Resource-pdf

- Wabanaki Life thousands of years ago (U.S. National Park Service). https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/wabanaki-life.htm

- Holding up the Sky: Wabanaki people, culture, history & art. Maine Memory Network. https://www.mainememory.net/sitebuilder/site/2976/page/4665/print#:~:text=For%20generations%2C%20Wabanaki%20people%20traveled,in%20the%20woods%20during%20wintertime

- Essay by Darren J. Ranco, PhD - Wabanaki Foodways and the State of Mainehttps://static1.squarespace.com/static/5dc48452ab6a5e7a070677aa/t/652417f4cd600e0f8a1dc638/1696864244899/Wabanaki-Foodways.pdf

- Maudrie TL, Caulfield LE, Nguyen CJ, et al. Community-Engaged Development of Strengths-Based Nutrition Measures: The Indigenous Nourishment Scales. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024;21(11):1496. Published 2024 Nov 11. doi:10.3390/ijerph21111496

- Luger C, Collins T. The Seven Circles: Indigenous teachings for living well. New York, NY: HarperOne; 2022.